Dismantling Harm Reduction and Emboldening Carcerality: Fuel for the Overdose Crisis

August 31 was International Overdose Awareness Day, which is an annual recognition of the harms caused by drug overdose. The campaign reminds everyone of the urgent need for “action and discussion about evidence-based overdose prevention and drug policy.” But, as the day passes, recent actions by the federal administration, including the issuance of the Executive Order titled Ending Crime and Disorder on America's Streets, endanger the progress achieved in the fight to end drug overdose.

The overdose crisis, as well as the houselessness and mental health crises, require evidence-based approaches grounded in harm reduction, not carceral tactics that deny the humanity and dignity of underserved communities. These destructive methods will only intensify the tragedies caused by the overdose crisis, especially for Black, brown, and Indigenous people, which are acknowledged by International Overdose Awareness Day.

Renewed attacks on harm reduction

Although drug overdose rates have decreased in recent years, they remain significantly higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic in nearly every state. In preliminary estimates, 77,648 people died from drug overdoses in the 12-month period ending in March 2024, translating into one person dying from an overdose about every 7 minutes. Among people experiencing houselessness, the overdose crisis is a profound concern due to systemic barriers, including structural racism and the unstable drug market.

As the overdose crisis has persisted, racial disparities in overdose rates have broadened. While the overdose rate for white people increased by 57.1% over the last two decades, the overdose rates skyrocketed by 249.3% for Black people, 166.3% for Indigenous people, and 171.8% for Latino people over the same period. In 2023, Black and Indigenous people died from overdoses at about 10 times the rate of Asian people, the group with the lowest fatal overdose rate.

Strategies based in harm reduction have been essential in the fight against overdose. Harm reduction refers to the philosophy of centering the humanity and self-determination of people within practices aimed at lessening the impact of oppressive systems. At the core of harm reduction is a recognition that people are marginalized from healthcare and other systems by racism, sexism, classism, and other systems of oppression. Harm reduction has the potential to reach people impacted by these interlocking systems of oppression and provide meaningful, compassionate care.

This philosophy is behind efforts to expand access to naloxone, increase availability of sterile syringes and drug use equipment, and reduce barriers to medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD). Community-based overdose education and naloxone distribution programs, for example, have been associated with substantial reductions in fatal overdoses.

Last month, the Trump administration launched an extensive attack on harm reduction within an executive order. Alongside ceasing support for harm reduction research and programming, including Housing First initiatives, the order threatens criminal, civil, and other punishments for programs offering life-saving harm reduction services.

The order was followed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) issuing a “Dear Colleague” letter attempting to redefine harm reduction to exclude naloxone provision. Despite the administration’s assertions, community-based organizations, including Chicago Recovery Alliance, and health departments have distributed naloxone as a core harm reduction strategy for decades. These programs emerged from the foundational idea that people who use drugs deserve full access to resources and tools that will protect their health and well being.

Involuntary confinement as a racist alternative without evidence

In place of evidence-based harm reduction practices, the administration turns to involuntary confinement, commonly referred to as civil commitment, to address the houselessness, mental health, and overdose crises. Involuntary confinement is the process of detaining people living with stigmatized health conditions, such as HIV, a substance use disorder, or a mental health disorder, based on the perceived danger posed by the person.

The executive order describes actions to increase technical assistance for state and local governments implementing these programs, reverse judicial precedents limiting the use of involuntary confinement, and screen more people for involuntary confinement through federal law. It also emphasizes the importance of the enforcement of loitering, squatting, and drug laws.

As a strategy to improve health, involuntary treatment is ineffective. Forced treatment for mental health conditions has been shown to provoke fear, stress, and distrust, potentially contributing to reduced engagement in health services and undermining public health. Medical distrust linked to involuntary treatment is especially destructive for younger people who may be discouraged from seeking out care or disclosing harmful ideations due to fear of punitive consequences such as involuntary treatment.

Involuntary confinement also depends on systems that lack adequate access to comprehensive health services for substance use disorders, mental health disorders, and other diagnoses. People may be confined in prisons or other facilities intertwined with the criminal legal system. Despite the increased number of people living with a substance use disorder in the criminal legal system, access to medication, including medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) such as buprenorphine, remains significantly restricted in jails and prisons across the United States. These shortages are partly driven by discriminatory policies and practices that deny or restrict treatment in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Regarding drug use outcomes, a systematic review of compulsory treatment showed no evidence of reductions in harmful substance use or overdose risk but noted the rights abuses prevalent in these models. Rather, the use of involuntary treatment through forced treatment has been associated with a 41% increase in nonfatal opioid overdose in the 30 days following release.

Additionally, the application of involuntary confinement schemes disproportionately affects Black, brown, and working-class communities. A study of a psychiatric treatment program revealed that Black people were 57% more likely than white people to be involuntarily detained. Moreover, economic vulnerability, including unemployment and receipt of government benefits, has been linked to a significantly greater risk of involuntary confinement.

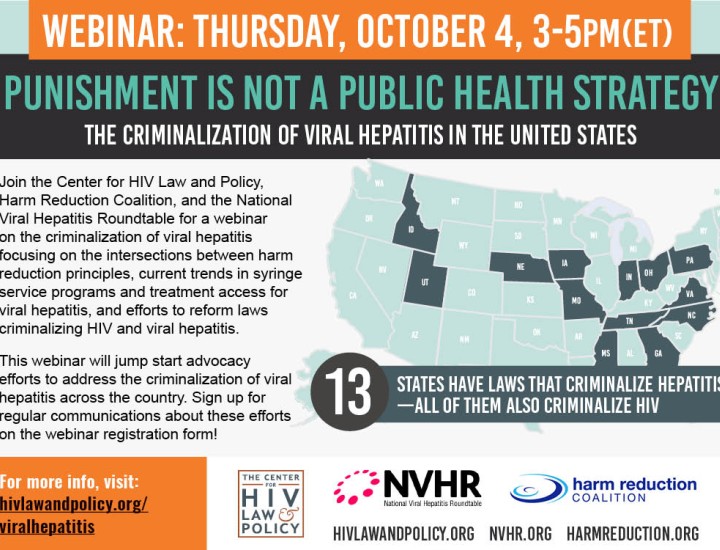

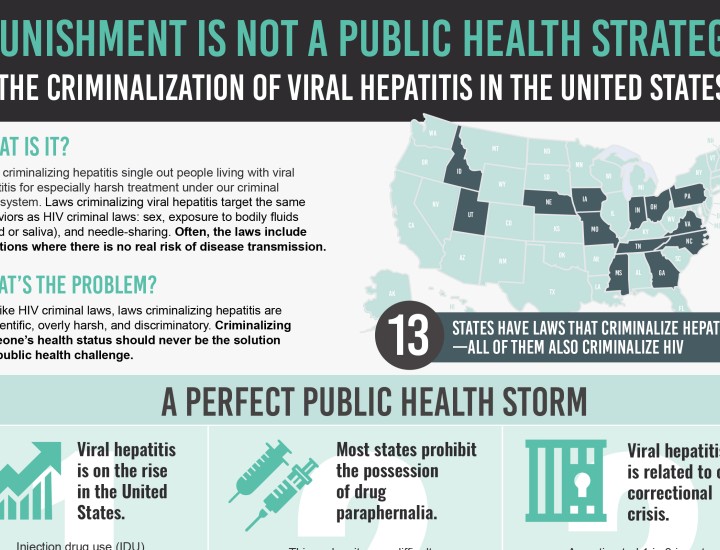

Racial disparities in the implementation of involuntary confinement schemes are consistent with the historical practice of control and punishment of Black and brown people through HIV criminalization laws and other punitive laws and policies. These carceral tactics are rooted in racist, classist, and sexist stereotypes regarding the inherent danger that Black, brown, and working-class people pose to society. As such, critics of the involuntary treatment scheme have noted the ways the strategy advances white supremacy, ableism, and other oppressive systems.

These ethical and effectiveness concerns have caused many, including medical professionals, researchers, legal experts, and disability rights advocates, to denounce involuntary confinement as an approach to the overdose and other health crises.

The resurgence of carceral approaches like involuntary confinement

The executive order is emblematic of a reemergence of involuntary commitment to address the converging crises of houselessness, overdose, and mental health diagnoses. Officials across the political spectrum, including leaders broadly opposing the administration’s other actions, have increasingly turned to involuntary confinement. Within these campaigns, leaders have positioned compulsory treatment as a more compassionate alternative to criminalization.

In the past year, for example, New York Governor Kathy Hochul proposed amending the statutory scheme allowing for the involuntary detainment of people living with mental health conditions. These changes would have removed the requirements that petitioners demonstrate the person living with a mental health condition posed an “imminent risk” or conducted “recent overt acts.”

Other efforts have resulted in substantial expansions in the power to involuntarily incarcerate people living with stigmatized conditions. In 2023, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed legislation broadening the definition of “gravely disabled” to allow for the detention of people living with alcohol and other substance use disorders. The law requires a consideration of the person’s ability “to provide for their basic personal needs for food, clothing, shelter, personal safety, or necessary medical care.”

More recently, Governor Newsom has also pushed state officials to develop plans to crack down on encampments and has urged localities to ban encampments. Last week, he continued these efforts through the launch of a state task force aimed at “targeting” encampments and clearing people from state property. These efforts have disrupted the lives of people experiencing houselessness, exposing them to the negative effects of the criminal legal system, endangering access to medications, and undermining mental health.

The use of these harsh tactics ignores the primary drivers of these public health crises and punishes people for the inadequacies of the systems aimed at addressing them. A study conducted with people experiencing houselessness in California found that insufficient housing and exorbitant housing costs were leading causes for houselessness. The report also found that people could not access treatment to manage SUD because of long wait times, disrespectful or unhelpful staff, or fear of “losing custody of their children” due to seeking help.

Demanding solutions to address the overdose crisis

With more than 75,000 people dying annually, including a disproportionate number of Black and brown people, the overdose crisis remains a prodigious public health concern, despite recent reductions in fatalities. The ongoing overdose crisis, as well as the interconnected houselessness and mental health crises, are the product of institutional failures, not individual people. They are the consequence of systemic disinvestment in evidence-based public health programs and the reinvestment in carceral punishment.

The recent actions by the federal government, as well as state and local officials, threaten to undo any realized progress in the fight to end overdose. By attacking public health strategies based in harm reduction and emboldening carceral approaches, the administration’s approach will make it less likely that marginalized communities will be able to access treatment and support services and more likely that people will be forced into carceral facilities against their will.

Involuntary confinement and other punitive strategies do not promote and protect public health; they expose people to harm. Despite being positioned as an alternative to criminal legal strategies, these approaches perpetuate the same negative consequences of the carceral system and fail to address structural determinants of health. The continued and expanded reliance on these methods will only exacerbate the carceral system’s harms against Black, brown, Indigenous, and working-class people.

On International Overdose Awareness Day and every day, there must be a renewed commitment to proven strategies that prioritize the self-determination and dignity of people affected by the overdose epidemic. Government leaders must reject destructive strategies that will only further stigmatize, marginalize, and isolate communities most impacted by these crises, especially amid widespread attacks on public health research and programming. Approaches grounded in harm reduction are vital for creating community, reaching people excluded from healthcare and other systems, and transforming care to effectively meet the needs of people most impacted by overdose.